Posted: 28/10/2019

In June 2019, it was reported that Liverpool Football Club wanted to register ‘LIVERPOOL’ as a UK trade mark for a range of football related goods and services. The trade mark application received substantial opposition from local traders and businesses, as many felt that the club should not have exclusive rights to use the word ‘LIVERPOOL’.

Several oppositions later, the club eventually withdrew its trade mark applications on 2 October 2019. This article analyses the likely reasons for this and the surrounding controversy.

In June 2019, the club filed trade mark application UK00003408413 for the word mark ‘LIVERPOOL’ in classes 9, 16, 25, 28, 35, 38, 41 and 43 (the main application). The specification covered a broad range of goods and services that primarily related ‘to the sport of football’ or were ‘in connection with a football club’.

In August 2019 the club divided the main application so that it was limited to classes 9, 25 and 28 only, generating a separate new trade mark application UK00003418051 covering the remaining classes 16, 35, 38, 41 and 43 (the sister application). Whilst the club’s motivation for dividing the main application is unclear, division is commonly used when applicants anticipate certain classes proving more problematical than others, and want to secure prompt registration for the less problematical classes.

The main application was subsequently accepted for publication by the UK Intellectual Property Office (the UKIPO) but, once published, generated more than 50 Notices of Threatened Opposition by concerned third parties, culminating in the main application’s voluntary withdrawal by the club on 2 October 2019.

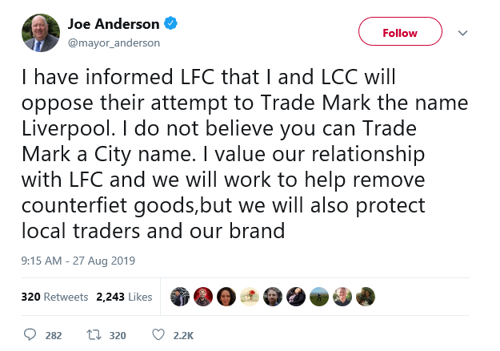

The City of Liverpool’s Mayor Joseph Anderson OBE, confirmed in a tweet that he and Liverpool City Council would both be opposing the club’s application(s):

In addition, Liverpool is home to numerous other football clubs, including Premier League side Everton , and non-league team City of Liverpool Football Club. Both of these clubs were also said to be unhappy with Liverpool FC’s trade mark applications and may have been amongst those who lodged Notices of Threatened Opposition against the main application.

By contrast, the sister application was refused by the UKIPO during the examination phase and did not therefore proceed to publication. Whilst the grounds of refusal are not publicly accessible via the UKIPO’s online records, it is probable that the application was refused on the grounds that it was (at least) descriptive (of goods and services originating from or connected with the city of Liverpool) and non-distinctive (given the descriptive nature of the word LIVERPOOL and its widespread usage by third party traders), and did not therefore qualify as a registrable trade mark within the provisions of section 3(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994.

On 26 September 2019, the club confirmed in a statement on its website that its sister application had been unsuccessful , stating that the decision was primarily due to ‘the geographical significance of Liverpool as a city in comparison to place names that have been trademarked by other football clubs in the UK’.

The club’s CEO reiterated that the reasons behind the trade mark applications were ‘in good faith and with the sole aim of protecting and furthering the best interests of the club and its supporters’.

The sister application was subsequently withdrawn by the club in tandem with the main application, on 2 October 2019.

The club’s statement mentions that other football clubs in the UK have been successful in registering place names as a trade mark. Examples include (ironically) the club’s arch-rivals, Everton (UK00002149693, UK00002598819 and UK00003071660) as well as Chelsea (UK00002381367, UK00002473289 and UK00003056529), Tottenham (UK00002130740 and UK00002582459) and Watford (UK00003017046). These registrations (and numerous others) demonstrate the clear value of such protection, particularly when it comes to taking action against counterfeit and unauthorised club merchandise, and show that the club may well have had the best of (legal) intentions in filing the applications, but had not fully considered or anticipated the public/local backlash that ensued.

The registration of geographic names has long been a contentious issue in trade mark law and will no doubt continue to be so. What can be said though, from the above examples, is that the more confined/localised/obscure the geographic reference/name is (as regards the goods and services in question) the less likely it is to face an objection from the UKIPO.