There are many reasons why young people choose to cross borders, and particularly the Atlantic, to embark on their undergraduate careers. The result is a growing number of cross-border families with a global footprint. Laura Dadswell, Partner and Co-Head of Private Wealth at Penningtons Manches Cooper, says: “When it comes to successful people and their children, it is of utmost importance that the next generation can access the best education available, even if that means looking outside of their home country.

“Among my own clients, I see children getting offered places at Oxbridge and choosing Harvard instead. Sixth-formers are now actively looking to the Ivy League as an alternative, and that has interesting long-term implications for the cross-border nature of those families.”

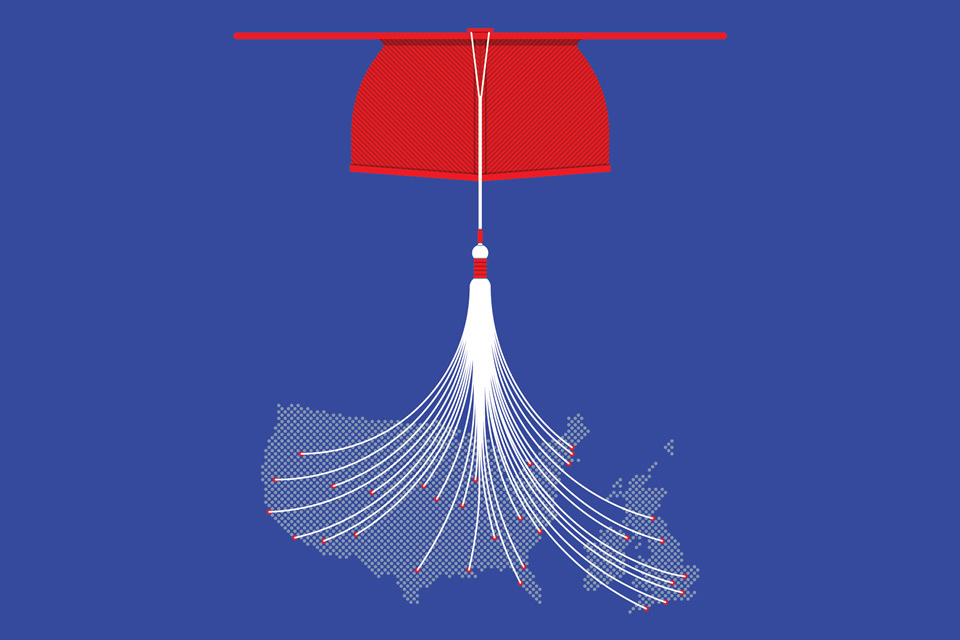

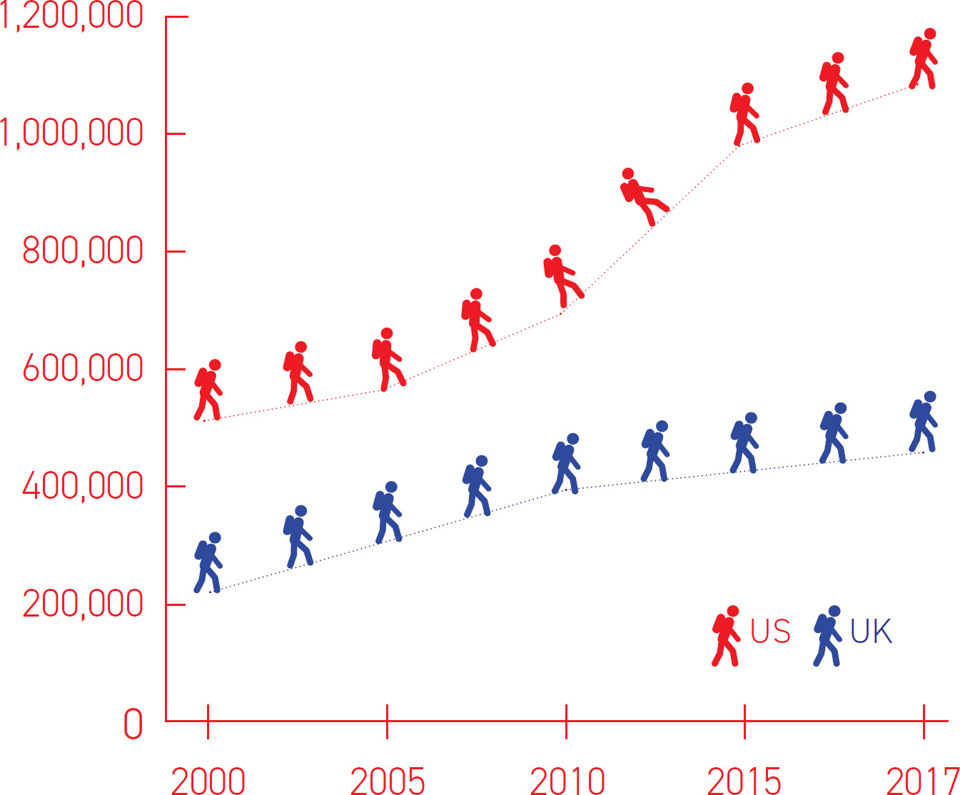

The number of international students attending university in the UK is increasing at a rapid rate. Official statistics show there were 460,000 international students in the country in 2017/18, an increase of more than 100,000 in just a decade. While the top country of origin continues to be China, young people from America make up a significant proportion of the British student population, with 18,885 US students choosing to study in the UK.

The UK is second only to the US when it comes to its international student population. Nearly 5% of all those enrolled in higher education in the US are international students, with the number growing fast – in 2018 the figure for international students surpassed a million for the third year in a row, according to the 2018 Open Doors report on international educational exchange.

“US admissions officers try to build well-balanced classes and look at what else you can offer – what you do in your free time, what your worldview is, what matters to you.”

Heading to America

There are many reasons why the brightest UK school leavers are starting to look beyond Oxbridge when considering where to apply. Higher education in the US takes a wholly different approach, starting with the admissions process.

Rowena Boddington, Director of Advising and Marketing at the Fulbright Commission, a non-profit organisation that is part of the EducationUSA advice service, says: “You apply for entry to the university, and not to a course, so you don’t have to know what you want to study when you enter.”

Degrees last for four years rather than the usual three in the UK, and students take a range of classes in the first two years before deciding towards the end of the second year what they want to pick as a ‘major’ for graduation.

Because applications are sent to institutions rather than subject departments, there is no limit to how many applications a prospective student can make, though Boddington says six to 10 well-considered applications is typical. “In the UK, university admissions are about your academic results,” says Boddington. “US admissions officers try to build well-balanced classes and, in addition to your academics, look at what else you can offer – what you do in your free time, what your worldview is, what matters to you.”

While admissions teams have their choice of applicants, students also have their pick of universities – there are 4,500 of them across the US. While the eight Ivy League universities are the best known, there are plenty of other high-quality institutions to choose from. Boddington names Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, Tennessee’s Vanderbilt University and Duke University in North Carolina. “They are all looking for top students, but they are not necessarily household names in the UK,” she says.

There are many parents that feel crossing the Atlantic to study will better equip their children for future careers and to prosper as genuinely international individuals.

To be a British undergraduate

For the thousands of overseas students interested in undergraduate study in the UK, there are 164 universities to choose from, 24 of them members of the elite Russell Group. Within that, there is the ‘golden triangle’ – Oxford, Cambridge and the top London universities.

The British higher education system is standardised in several areas. Tuition fees are set by the Government for domestic students, while the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS) allows global applications through a central system. Candidates can pick up to five courses at as many universities; for those wishing to apply to Oxford or Cambridge, it is not possible to apply to both in the same year.

One benefit of pursuing undergraduate education in the UK is the proximity to London and the rest of Europe for travel and internships during or following university, as well as for networking opportunities. The capital, with its 40 higher education institutions, offers a unique student experience. At the London School of Economics (LSE), 60% of students are international, in a city where over 300 languages are spoken. “You get to encounter ideas from all over the world as part of your daily life,” says Laura-Jane Silverman, Head of LSE Generate, the university’s entrepreneurship centre. “In a globalised world, that kind of international perspective is invaluable,” she adds.

Global citizens

Dadswell says the number of wealthy families from across the world that choose to send their children to the UK and the US for higher education creates an interesting, and growing, footprint of western culture. “Whether you are talking about China, India, Russia, LatAm or elsewhere, you see those children going back to their home country on graduation with a much more western approach,” she says. “The US/UK-educated generation will come back home with a different attitude to managing family money, protecting assets, dealing with succession of family businesses and accepting things like divorce. Not surprisingly, we see an increasing appetite globally for private wealth advice based on principles developed in the US and the UK”.

There is also a growing likelihood that students put down roots in the country in which they choose to study, perhaps meeting a potential life partner while at university, establishing a career straight after graduation or buying a house there. Likewise, it is not uncommon for parents to purchase second homes in the countries where their children have chosen to study, either to facilitate easy visiting while the child is away from home, or to provide student accommodation.

Such cross-border moves create a raft of legal issues that require consideration, not least the requirements for visas and the potential tax implications of living and working in a second jurisdiction. Students who settle in the US in particular will need to be mindful of assuming ‘accidental American’ status and becoming liable for taxation under the US system.

Pat Saini, Partner and Head of Immigration at Penningtons Manches Cooper, says: “We are often assisting clients with children who are thinking about applying to attend university in either the US or the UK. People often don’t realise that you need to apply for visas in plenty of time. It’s much better to talk to us and gain an understanding of the process early on so there isn’t a last-minute panic.”

Talking fees

The cost of a university education varies enormously around the world, just as the approach to education funding differs between countries. Dadswell points out that the education funding culture is often the first noticeable difference for British parents looking at further education abroad: “Wealthy families in the UK are used to spending money on secondary schooling up to the age of 18 and they expect education after the age of 18 to be much cheaper. In the US, it’s the other way around, so the structuring is quite different,” she says (see box).

What price an education?

For those used to paying British boarding school fees of up to £16,000 a term, a British university education looks cheap, with tuition fees of £9,250 per year set by the Government for all institutions including Oxbridge.

In the US, fees vary from university to university: all-inclusive Harvard fees currently ring in at $67,580 per year, while at Boston University, tuition, board and room costs $43,810.

What is clear is that, for those with the means to choose the very best available for their child, an ever-increasing number are opting for an international experience. In so doing, they are creating a next generation of cross-border nationals who will grow up with a far more international perspective, often calling more than one country home.

Back to Edition 1 - The united issue

Back to Edition 1 - The united issue

Back to Edition 1 - The united issue

Back to Edition 1 - The united issue